Contents

The Priest Chalice, the vase that contains Christ’s Blood during a Mass. Symbol of communion between God and men, of the salvation incarnated in Jesus.

The chalice is the sacred vase containing the wine that turns into Christ’s Blood during Eucharist. It symbolizes the chalice Jesus used during the Last Supper, therefore a normal glass. In fact, the Latin word calix means glass, cup, a common object in every house. Private houses were the first places of cult for Christians; it is therefore obvious that they used a normal glass to consecrate Liturgy wine.

The Chalice is then a symbol of the communion between God and men, of the ancient alliance of the Old Testament, which renovates and gains a totally new meaning through Jesus’ sacrifice. His blood, offered to atone for all sins, becomes symbol of Jesus son’s obedience on one side, and the mean of salvation for all men on the other side. Through consecrated Bread and Wine during each Mass, that sacrifice is renewed, as is the communion that saw apostles eat and drink during the Last Supper, becoming integral part of that immense Mystery.

It is therefore obvious that the chalice for the Communion owes its importance mainly to what it will contain, that is, the wine turning into blood. But it also carries its own intrinsic symbolic value, since it recalls the cup Jesus used during the Last Supper, that Holy Grail that is the main character of many wonderful legends and stories passed on throughout centuries.

The same can be said for all other sacred furniture Priests use during the Liturgy. Next to the communion chalice, we can find the pyx, the chalice for the hosts (even if it can also be a bowl), which will contain the consecrated particles; the ampullas, usually in glass, which contain water and wine before they are poured: the paten, that is, the plate where the priest places the biggest host during the Consecration. There are also textiles, equally important for the ceremony: the corporal, which is the starched square cloth placed on the altar to receive Christ’s Body; the pall, a small starched cloth that covers the priest chalice; the purificator, a napkin used to cleanse the chalice and the paten after the communion; the manuterge, used by the priest as towel.

The Liber Pontificalis, a list of biographical notes written in chronological order about the Popes who seated on the Papal throne until the end of the IX century, often names the priest chalices, dividing them into calices and scyphi, depending on the use they were destined to: the consecration of wine, the distribution of Eucharist, or just as votive decors.

According to the Liber Pontificalis, chalices could be catalogued according to different features, and be:

- maiores o minores, depending on size:

- sacri o sancti, if used for consecration;

- ministeriales, if used to distribute the Communion to the devotees;

- offertorii, if destined to contain the wine to consecrate;

- quotidiani, for daily and non-festive use;

- stationales, used during functions of station rites;

- ad baptismum, for new Christians;

- pendentiles o appensorii, merely votive and decorative objects.

Later, in the XII and XIII centuries, the followings were added to the list:

- ad communicandos infirmos, to distribute the Communion to the sick;

- viaticus, a smaller, travel chalice;

- funerarius, to ornate priests’ tombs.

Here is a further, more modern and generic, cataloging of chalices:

- Chalice with handles: big, with two handles, popular in the Carolingian age;

- Chalice with bells: decorated with bells falling down from the cup or the base, popular in Spanish countries;

- Chalice for foretaste, small, with handles and lid, used to taste wine before the Mass;

- Missionary’s Chalice: small, suitable for long journeys;

- Seminarist’s Chalice: not consecrated and made of non-precious materials, it is used to teach seminarists how to celebrate a Mass.

- Funerary Chalice: as the already mentioned funerarius, it was small and light, made of humble materials such as wood, lead or tin, and was put into priests’ tombs;

- Papal Chalice: reserved to the Pope, it has a lid covering it;

- Purificator Chalice: until the XVII century, it was used to offer devotees who received the communion some non-consecrated wine to rinse their mouth;

- Viator Chalice: small, sometimes it can be disassembled, used during journeys.

How a liturgical chalice is made

The priest Chalice has evolved a lot in style throughout centuries, changing its shape from a sort of bowl in clay or glass to wonderful and precious chalices, going back again to humble objects, and then again through an artistic blooming between the Renaissance and the 19th century, becoming a true piece of jewelry and integral part of the treasures of churches and cathedrals.

The first calices or scyphi were made of gold or silver, often cantilevered or chiseled, and ornated with pearls and gems. After the year 1000, the liturgical rite was simplified more and more, and the habit of offering wine to the devotees completely disappeared. Even the shape of the chalice became more basic. Romanic chalices looked like large and shallow cups, almost semi-spheres, and laid directly on their knop. The stem and the base were replaced by an upside-down bell. During the Gothic period, chalices became taller: the cup was smaller, the stem was longer and enriched with decorations, and the knop laid on a decorated foot.

In the XVI century, the priest chalice went through another reduction in style. The cup was countersunk, the stem egg-shaped and the base circular. Symbols of the Passion were added to the late-Renaissance decors.

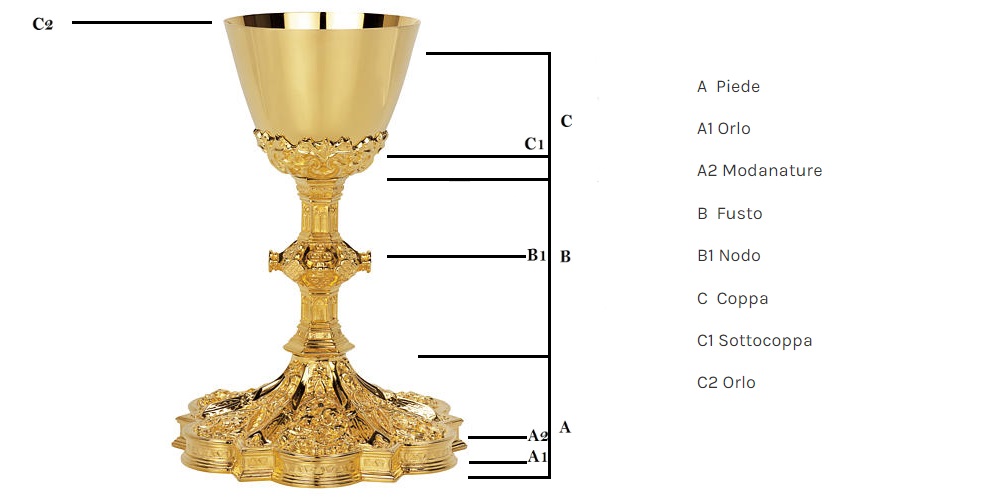

The modern priest Chalice is shaped like a countersunk cup, and is made of three parts: the foot, the stem and the cup. Its lines were furtherly simplified; decors are the same neo-Gothic or Baroque ones, mainly symbols recalling Eucharist and Passion.

The foot of the communion chalice is usually round, but can also be polygonal or have a complex shape made of lines and curves. The important thing is that it is big enough to guarantee stability to the whole structure. That is why it has to be larger than the cup.

The stem can be of various length, but it is usually proportional to the other elements. It is interrupted by a knop, an element that is both decorative and helpful to the priest for handling the chalice during the consecration.

The shape of the cup must consider its purpose. It must not be too deep and a bit long in its final part where the priest will lay his lips.

The size of the priest Chalice

The priest chalice must have specific measures, defined by the Canonical Visitation in Rome in 1904: it must be at least 16 cm, but no more than 28 cm. A good average for an everyday chalice is around 22 cm, with a cup of at least 25 cm diameter according to Saint Charles Borromeo. Chalices made following a particular artistic care can be up to 27 cm, and the cup can be of 32 cm of circumference.

Travel chalices, and the missionary, can be a bit smaller since they need to be carried easily. In that case, 15 cm is acceptable.

Materials a sacred chalice is made of

At the beginning, the Church used common chalices and cups of glass, but they soon began creating chalices for masses with decorations of Christian symbols, and most of all precious materials such as gold, silver, agate, onyx, marble, etc…

In the early medieval age, they went back to use less noble materials besides stone, horns and wood.

Today liturgical rules impose that at least the inside of the chalice cup is made of a precious metal, gold or silver, or at least gilt on the inside. That because it is destined to touch Christ’s Blood or Body.

It is forbidden to use a non-noble metal for the cup, which may break or ruin easily, such as clay, bronze, glass or wood.

Brass is accepted, even though it is not noble, but it is resistant and does not break easily, as long as the internal gilt is replaced when oxidation begins.

The material used for stem, knop and foot is instead irrelevant. Tin is very popular because it has the pro of being cheap and resistant.

The style of the priest Chalice

Priest chalices can be divided into four categories, depending on the style they are made:

- baroque style

- Neoclassical style

- medieval style

- simple style

The Baroque chalice comes from the 19th century chalices, finely chiseled and often decorated with angel heads and other very rich decors. Its height goes from 27 to 30 cm.

The Neoclassical chalice draws inspiration from neoclassical models, with linear and not elaborated decors. Its height is between 25 and 27 cm.

The medieval chalice recalls the Gothic art with complex chiseling, embossing, repoussage and low relief. It’s about 25 cm.

The simple chalice is more modern, with clean and thin lines, but rich in chiseling. Its height is between 25 and 28 cm.